Three years ago, on 2/6/2019, I had corrective surgery to fix the cochlear implant in my left ear. Back in 2016, the original surgeon had not inserted it correctly. I shared my story before about the painful long 3 years (2016-2019) that I lived with a problematic implant (a tip fold over). I went into the corrective surgery with hopes and expectations that the issues I had suffered with would be easily fixed.

That isn’t what happened. I went to Vanderbilt University for the operation. My surgeon, Dr. Robert Labadie, is one of the best in the field and often has dealt with cleaning up messes that others have made. He told me in my pre-op appointment the day before that while indications were that it would be a smooth revision surgery that would hopefully take less than an hour and I would be released the same day, he was prepared for anything when he opened me up.

He wasn’t kidding. When he opened up my left ear in the OR, he was expecting to simply remove my old implant (electrode array) and insert a new one. Instead, what he found was immense damage in my cochlea that led to a difficult extraction. Because I lived for 3 years with a severe tip fold over, the stimulation had been focused in a small, concentrated area of my cochlea and had traumatized those tissues. Every sound for 3 years. That’s a lot of trauma.

My body had been doing an amazing job of trying like hell to protect me from that trauma. The way it tried to protect me was to ossify and turn to bone the area where the original implant was inserted. Dr. Labadie discovered that the original electrode array was embedded in bone. In order to remove it, he had to drill to get it out. This also meant he would not be able to insert an implant (a new electrode array) as is traditionally done. It also meant that the part of my cochlea that had ossified would not be usable. This was a very important part, as it was where the tissues and neurons for low frequency sounds are biologically located.

He realized in the OR that if he was going to save my left ear, he would need to get creative. Very creative. He was very determined to do what he could to save my left ear. He went about trying a few different methods to get an implant in to the other parts of the cochlea. He knew it would be less than ideal and it would be an uphill battle to give me complete access to sound. But also that if he could get the implant even partially inserted, it would likely still be better than what I had been living with for those 3 long years.

He went to work. After trying a few different approaches, he landed on drilling into my head to literally carve out a new opening. He persisted and eventually was able to partially insert a new implant. The implant is made up of an electrode array with 16 electrodes. The ideal placement of it in the cochlea is to touch on the tissues with associated neurons to cover sound from the low to high frequency range and have the full electrode array inserted with 16 electrodes to work with. Unfortunately, the ossification and bone growth mean some of those tissues were not going to be touched on and he would not be able to achieve a full insertion.

The new pathway into my ear was accomplished by literally moving my balance nerve to access the cochlea. He drilled and was able to get the new implant partially inserted. He was able to accomplish this in part with the aid of intraoperative CT imaging. The Vanderbilt Cochlear Implant group has been advocating for CT imaging to check implant placement for some years. He had this set up in the OR and made use of it to help in saving my left ear.

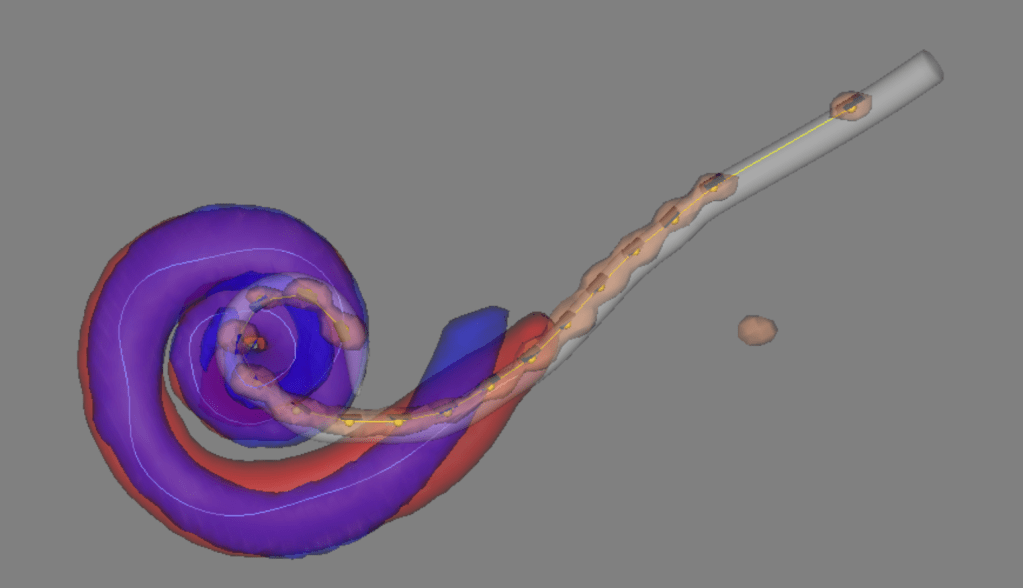

Specifically, he was able to insert 8 of the 16 electrodes. The following image shows 8 of the 16 electrodes inserted and touching on some areas of the cochlea:

Yup. It’s not pretty. It shocked me the first time I saw it.

When I awoke in recovery after the 4-hour surgery, the first words out of my mouth were “what happened??” I felt broken and not right. Granted, I was obviously drugged and still under the effects of anesthesia. But my core felt obliterated.

Dr. Labadie was there in recovery. He told me that it had taken 4 hours to do the surgery and there was immense damage. He said mine was the second most difficult surgery he had ever done. He explained that he had to move my balance nerve to gain access and only achieved a partial placement. And he told me that he did the best he could and that I would likely hear better than what I’d had with the tip fold over. But he did not know how much better.

Laying in recovery, I broke down in tears. Hearing the news that he shared broke me. For those 3 long years, I experienced what it meant to essentially not have the use of my left ear. It was devastating and destructive for my ability to connect with myself and the world. In those moments in recovery, I feared I had lost my pathway to connection forever.

I also noticed how disoriented I felt when I looked at him as he spoke. I felt like my body was suspended in an open space without any orientation of what was up or down. It was extremely distressing, very unlike anything I had experienced before. I’d of course lived before through vertigo or dizziness, but this was a different experience entirely.

Due to the severity of the corrective surgery, out of precaution Dr. Labadie said he wanted to admit me to stay overnight. That turned out to be a good call, and I actually had a 3-4 day inpatient stay. After being moved to my room, a few hours later I awoke and tried to sit up. I immediately threw up on myself and had no sense at all of what was up or down. It’s hard to describe. I couldn’t even feel the bed holding my body in place. It was terrifying to lose spatial awareness, and to such an extreme.

Dr. Labadie saw how devastated I was and suggested I have my new implant activated (‘turned on’) the next morning after surgery. I think he may have recognized I needed some kind of hope and knew that activating it might help.

The next morning I was taken in a wheelchair (there was no way I could walk with the spatial disorientation I was experiencing) to my audiologist’s office, Dr. Jourdan Holder. She proceeded to turn on the implant. When she turned it on, it sounded really different from the problematic tip fold over implant. We talked more about it and she explained that the partial implant was providing stimulation to areas of my cochlea that had not been stimulated at all for over the past 3 years. And it was really up to my brain and neuroplasticity to sort out this new signal. It would be up to my brain to see if it could re-organize the mapping of stimulation to the neurons in a way that would give me access to sound at different frequencies.

A few days later I was released. Over the coming weeks, I tried many things to see how the implant was working. I played songs I’d listened to my whole life. I played recordings of my own voice from years before. Watched movies without captions to see if I could understand what characters were saying. In the first 2-3 months, I was discovering that I could almost make sense of some sounds. But things were not very clear and I was having trouble emotionally accepting that I had partially lost the use of my left ear forever.

It was a slow and gradual process and truthfully, I did not see the pieces coming together until they already had. By the end of 2019, 10 months later, and a few audiology visits with Dr. Holder, my speech comprehension had exponentially improved. It was bizarre and surreal. Especially since there is nothing linear about hearing. With just use of my left ear, my comprehension was 42%. With just use of my right ear, it was 52%. But combined, with both ears, I was achieving 95% speech comprehension (AZ Bio sentences in quiet). 95%!

By the time 2020 rolled around, I was able to listen to podcasts. Music was stabilizing and sounding good. But what was really most noticeable was my daily interaction with people. Some friends commented on how interacting with me had changed. After 3 years of struggling to hold a conversation or understand what somebody was saying, I now was conversing real time without needing things repeated and understanding very well. This changed my life. In many ways, it gave me my life back.

A downside to the revision surgery has been my balance. It was really off for the first year. I’ve tried to apply methods I have learned in my Eastern arts training over the years. Qigong and meditation have helped. In summer 2021 I returned to playing tennis, something I’d done when I was younger. That has helped to mend some of my eye-hand coordination issues stemming from the surgery. It isn’t perfect and I still fear being pulled over, asked to walk a line, and failing that test. Gulp. Alas. I’m working on it.

One of the hardest aspects of the past 6 years, something I have really struggled to deal with, has been the effects of the tip fold over of the original implant on my speech. Human speech is naturally based on a feedback loop. As a young child, we repeat what we hear. And as we learn to speak, what we enunciate is based on how we hear ourselves. The cost of living for 3 years with an essentially broken signal and severely fractured sound meant that what I heard and the way I heard myself was quite problematic. I’ve had to come to terms recently with the toll that has taken on my speech.

A powerful internal experience that I have struggled a lot with has been reconciling living with a broken signal and fractured sound. When the world sounded fractured, and I listened to myself speaking in the world, it fed into this feeling that I was broken and fractured. For example, when the pandemic began I joined a group of friends for frequent meditative practices and they involved sound or singing. I’d lead at times, and felt very self-conscious about how I sounded. It felt broken and fractured to me, and I was feeling like it was nearly impossible to separate the feeling of how I sounded with how I felt about myself. That has been a learning experience for sure, to work with those feelings and discern the two.

The tip fold over and issues with it resulted in my lacking a sensation or feeling of sound. I have recently been learning more about how my body had responded to that lack of stimuli from sound. In effect, my body reacted by changing the way I was producing and creating sound, in order to force a sensation. Much of the sound I was producing migrated from natural vibration in my mouth area to my nose. By moving the sound sensation to my nose, it enabled me to feel sound again. This was entirely unconscious, and I was not aware that this was happening. I did not even know until recently this was happening, or that I had been sounding nasal in my speech and voice.

I’ve discovered society has a label for this kind of reaction. It’s often labeled as deaf speech. When I first heard this label and term, my reaction was ouch. That hurts. I don’t like this label. At all. With my cochlear implants at this stage, while I have pretty good speech comprehension, I do not have an ability to detect subtlety in sound. I cannot actually even hear the nasality in my own voice. Or the slur and fact that I fail at times to clearly enunciate some words.

A few people, strangers I’ve met, have asked me if I have a Canadian accent. That still makes me laugh. I smile and say sure, that’s it. A few others have commented that it sounds like I have a lisp. Some have commented that I am difficult to understand at times. It hasn’t been easy to come to terms with my speech being and sounding different at this point. Some had said it isn’t a big deal. I like those friends. 🙂

I didn’t think there was anything I could do about it. But thanks to a friend, I recently connected with a voice coach and specialist, BettyAnn Leeseberg-Lange, which has been quite an amazing experience. I am working with her to learn about new pathways for managing and producing speech. BettyAnn has worked for many decades as an accent modification expert. She works with Lessac Kinesensic Training which is a theory founded by Arthur Lessac. His idea is to shift the frame of reference from producing speech using the feedback loop to a frame of reference of producing speech using sensation. The training has included learning to feel my mouth and tongue and internal vibration with each vowel and consonant. It’s been interesting to study this and amazing to have a pathway to speech that doesn’t require good hearing.

It’s been quite a ride. I’m very lucky to be as functional as I am with the limited hearing that I have. I’ve learned so much over the past 6 years. I’ve evolved with my understanding of the distinction between hearing and listening. My hearing is not perfect. Luckily, good listening doesn’t require perfect hearing. I get to use my whole being to tune in and listen to people and my environment. I certainly miss some spoken words and speech on occasion. But I fret less and less about this, and instead focus on what I do hear and notice.

This is interesting to me. In midst of this journey over the last 6 years of losing my hearing, receiving cochlear implants, the tip fold over, and a traumatic revision surgery, my professional life has gone very well. I received tenure, was promoted to full professor, and recently became department chair in my school. I am a professor in public health, which has been thrust into the spotlight during this global pandemic. With the help of captioning, I have been able work from home and conduct my classroom instruction, meetings, and collaborations, in the zoom environment without issue.

An upside to my whole experience was an opportunity to integrate my professional life with this experience. I enjoyed a fun and meaningful collaboration with Dr. Labadie, Dr. Holder, and some others at Vanderbilt University, to author a publication in the science and clinical journal Otology and Neurotology about the use of statistics in otology research. Our goal was to offer recommendations for how statistics are used to improve on decision making and conclusions from research studies. That was an awesome experience, and I am proud to see our work and recommendations in print.

When I posted my original story about my experience with the tip fold over, it was written just before going in for revision surgery. I received dozens of lovely messages and responses from friends and the CI community. A number of people asked me to share a follow-up on how I am doing. Thus, my penning this update.

If you made it this far, thanks for reading. My email address is martialsigning@gmail.com if you want to share your CI story or get in touch.

Happy hearing!

Matt

Leave a comment